This is a story written base on reflections my initial year after diagnosis (2016), with added comments about what I’m thinking after my second diagnosis (2024).

The feature image is from Wikimedia Commons.

Like my stories? Please subscribe.

Introduction

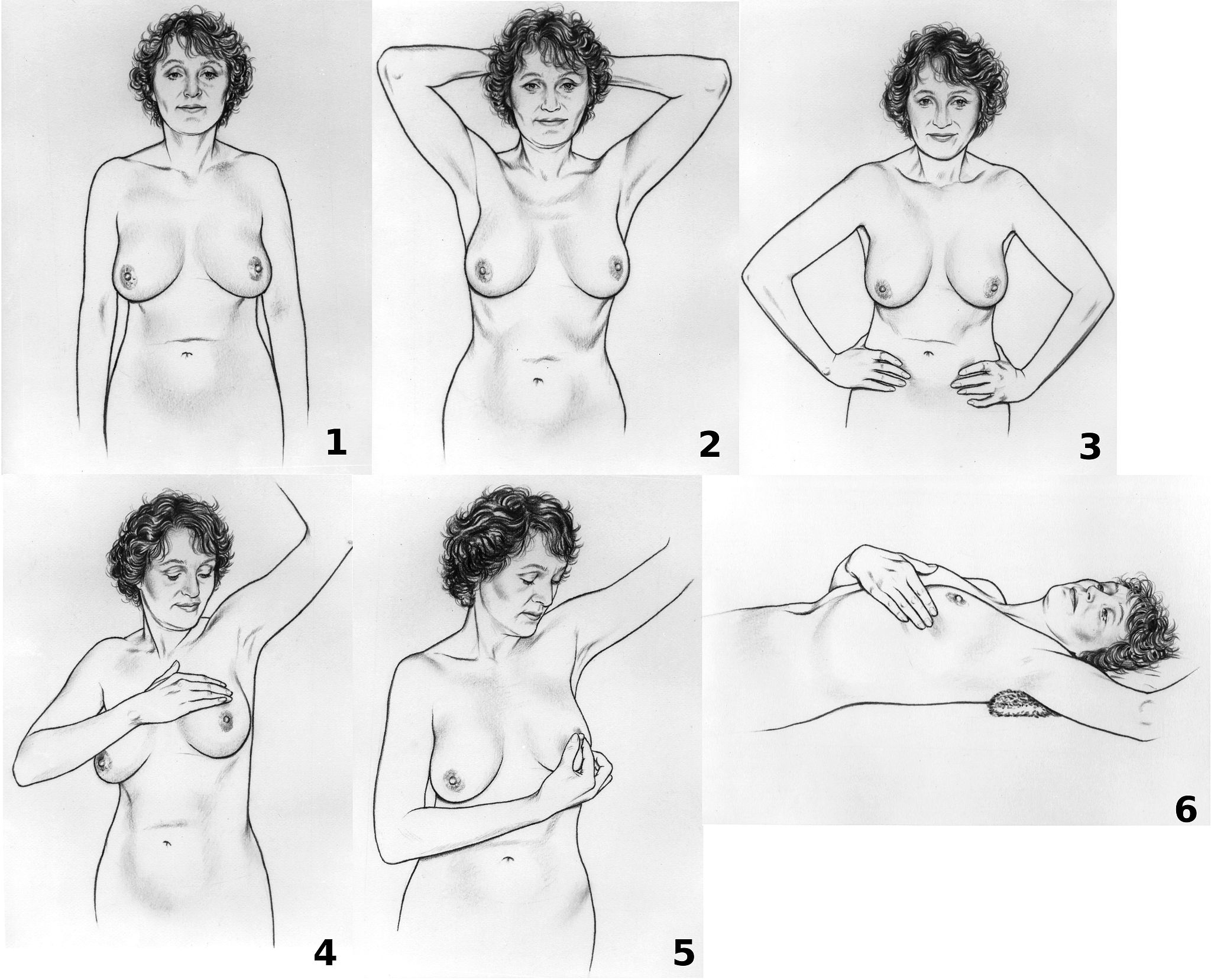

Before my first diagnosis, I was obsessive about breast self-exams. Every time I showered, I would check, feeling each part carefully. It was just part of my routine—not because I had any family history of cancer, but because of a high school health class. The nurse had brought in these dummy breasts with a “lump” we were supposed to find. I remember how I could never feel it, no matter how hard I tried. That really stuck with me. I was afraid that when it mattered, I wouldn’t feel anything.

I missed the lesson on looking for changes, not just lumps. Now I can tell you everything you should be looking for in a breast self-exam – changes, not lumps. However, only days after seeing initial changes, I felt a lump. I thought it was a muscle strain at first, but it didn’t hurt and it didn’t go away. It wasn’t a muscle strain, it was a 4.5cm tumour in my left breast.

~~~~ 2016 ~~~~

It has been a year since my diagnosis and treatment for bilateral breast cancer. I no longer have breasts. I have fat tissue that was transplanted from my stomach to make forms that look like breasts. The breast-self exams I did before don’t make sense anymore. I have no breast tissue. But I also have no sensation, which comes with new risks.

One of my new risks is the cold. I have body parts now—my reconstructed breasts, my belly—that I can’t feel. They’re living flesh, warm to the touch, but numb. I have to relearn what “normal” feels like, but also how to check myself to make sure I’m not getting frostbite.

I’m still exploring what a breast self-exam means for me now. This was how I found my cancer. I used to check every time I showered, and I saw the change almost immediately—a lump, and a strange discharge. But now, I don’t have breasts with breast tissue. My nipples are still there, but they don’t leak anymore. They’re unfeeling and unresponsive, but they’re warm to the touch.

I still examine my chest, but I’m looking for something else. No lumps—just damage. I’m scanning my skin for signs of anything that could have happened without me noticing, because I can’t feel it.

Part of my new normal is this constant exploration of my changed body. I trace the areas with no feeling, trying to find the boundaries—where sensation fades from something to nothing. I want to see if these boundaries shift. I’ve been told there’s a chance I might regain some feeling, but nerves can take up to three years to grow back. For now, I’m grateful it’s not winter. I’ll have at least a year or two, maybe more, before I need to think about what snow and freezing temperatures mean for my body.

~~~~ 2024 ~~~~

I am used to my body. My urge to inspect it so closely fades. I stop any form of breast exam in the winter. Now, it’s during the warmer months that I need to check. Instead of worrying about frostbite, I’m prone to heat rash, especially under my breasts. I don’t feel it when it starts; I only notice it later, after it’s become severe. By the time I see it, it needs days of treatment—creams and patience—to calm down. I can’t always tell if the creams are working; I just wait for the rash to fade.

I stopped looking for cancer years ago. Then came a regional recurrence, in my lymph nodes. They found it on a scan. I couldn’t feel the swollen nodes, even with a 2.5 cm tumour growing in the largest of the five cancerous nodes. My family doctor also could not feel it. That experience stripped away any faith I had in self-exams to detect recurrence. The familiar routine I once had, washing and inspecting my new breasts, has fallen by the wayside, offering no comfort now. All I can rely on are blood tests and scans.

My new normal feels like my old normal. After a shower, I give myself a quick glance in the mirror, just to check if anything looks wrong. That’s it. I don’t dwell on it. There’s nothing left for me to find. A self-exam in the shower isn’t going to catch cancer if it comes back. So, unconsciously, and now consciously, I’ve moved on from that practice.